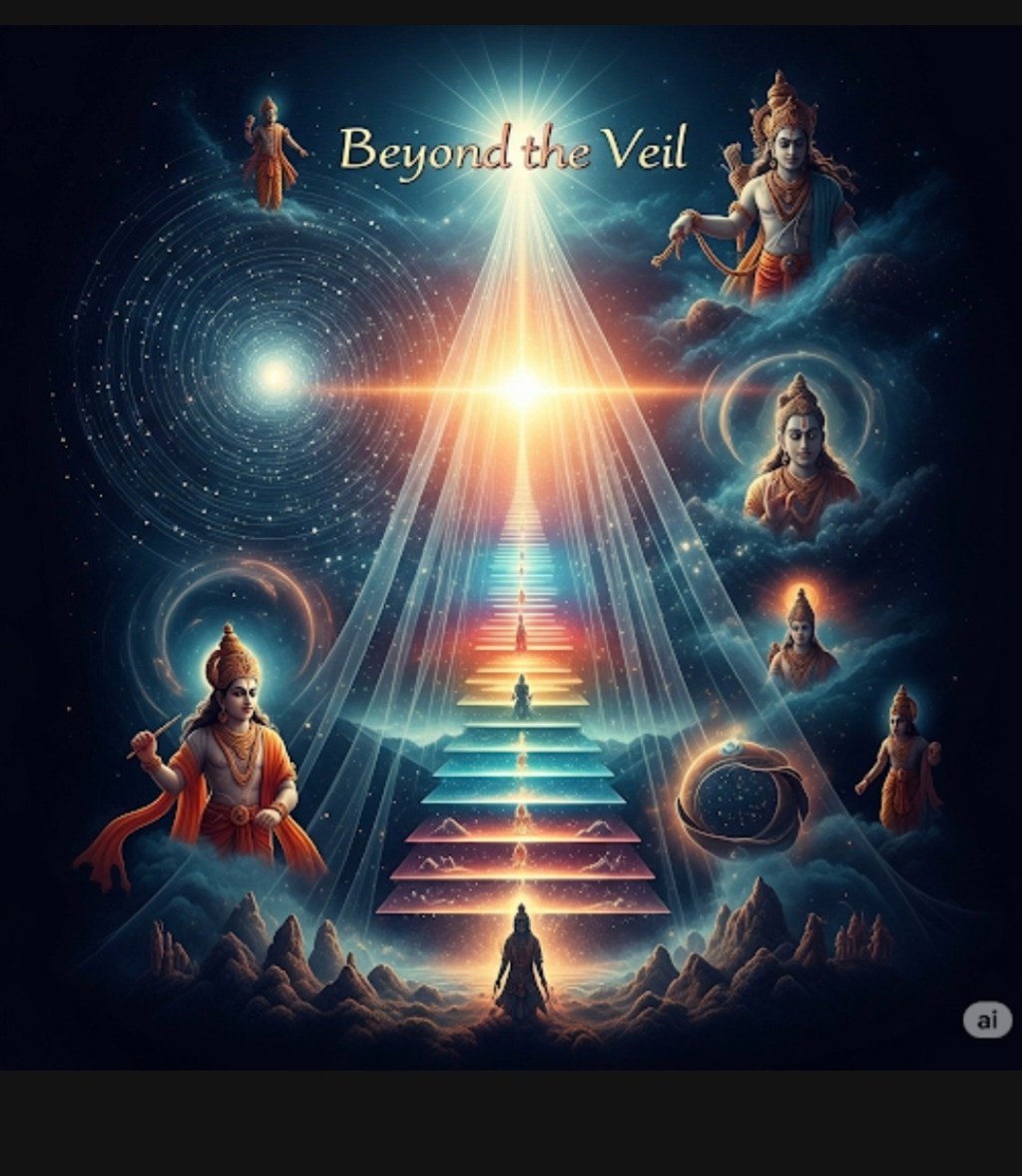

The spiritual journey, much like the grand epic of the Ramayana, is an intricate dance between what appears real and what truly is. We’ve explored how seemingly disparate concepts, from the fundamental nature of reality in quantum mechanics to the allegorical tales of ancient India, converge on a singular, profound truth: the ultimate nature of existence as non-dual Brahman, and the universe as its captivating, yet ultimately illusory, manifestation.

The Emergent Dance of Reality

We often perceive the world in distinct layers: fundamental physics, then chemistry, then biology, then complex phenomena like economics. But what if even “fundamental physics” is not the bedrock we imagine? Our exploration suggested that even the laws of physics might be emergent from a deeper quantum mechanical substrate. This quantum realm, all-pervasive and the source of everything we perceive or conceive, mirrors the very nature of Purushottama – the Supreme Being, ineffable and beyond description.

The concept of “Akshara,” or the impersonal soul, as an emergent phenomenon was a fascinating starting point. Just as economics arises from countless individual interactions, possessing properties not inherent in any single participant, so too might ‘akshara’ emerge from the underlying quantum reality, the Purushottama. This challenges the notion of individual immutable spirits contradicting non-duality. If everything is Purushottama, then the very ideas of multiplicity, mutability, or immutability become emergent, arising from a “nowhere” that we can equate with Maya or ignorance.

The Observer and the Illusion

This brings us to a crucial point: the role of the observer. Quantum mechanics, with its observer effect – beautifully illustrated by the Young’s double-slit experiment – reveals that reality is not entirely objective. The presence or absence of a measuring device alters the behavior of particles. This suggests that everything, including our subjective experience, is ultimately illusory, precisely because it depends on the observer and the time of observation.

Just as the world appears as Dvaita to some, Advaita to others, or Vishishtadvaita to still others, these interpretations are themselves emergent processes. They are as numerous as the observers, and thus, even the interpretations are ultimately illusory. This is why Purushottama cannot be described by words; as poet saint Jnaneshwar eloquently states, it’s like trying to catch air with a net. Purushottama is indeed inconceivable, non-inferable, and indescribable.

Brahman: The Basis of the Grand Illusion

If the entire observable world, including particle physics and the very act of observing, renders this world illusory, then there must be a basis for this grand phenomenon of illusion. A mirage, for example, has its basis in light. Similarly, this ultimate illusion, the universe, must have its basis in another form of divine light, Brahman. Everything rests there. Everything arises or emerges from there, and everything ultimately returns to that place after the phase of destruction. Brahman is the sole foundation and encompasses all possible illusions. However, just as light is separate from the mirage, which does not truly exist, Brahman remains separate from the illusory experience we have.

This leads to the profound understanding that any conceptualization, or even an attempt to conceptualize, is ultimately illusory. We can only ascertain Brahman’s omnipresence and existence by inferring the reality of the phenomenal world, which is itself an illusion.

Maya as the Act of Observing and the Path to Turiya

We can extend this further: Maya, to me, is the very act of observing. If we have a choice not to observe, which is akin to the fourth state of consciousness called Turiya in Sanskrit, we become Brahman. The other states – waking, dreaming, and dreamless deep sleep – are illusory because they inherently involve the observer “acting.” As Jnaneshwar explains, we get a strong sense of reality even while dreaming, unless we “wake up.” Similarly, the apparent reality and efficacy of our waking experience stem from Maya.

To break free from Maya’s grip, the Bhagavad Gita in its 15th chapter advises using the “sword of detachment.” Maya is equated to the metaphor of the Ashwattha tree, an inverted tree with roots in Uttama Purusha. This implies that while the illusion arises from the divine, our liberation comes from severing our attachment to its manifestations.