There’s a thread of inquiry that, once pulled, unravels everything. It begins with a simple question about the world and ends by questioning whether there is a “me” to even ask it. This is the story of that unraveling, a complete philosophical arc from the absurdity of objects to the dissolution of the self.

The Dangling Pointers of Reality

It started, for me, with numbers. How can a ‘7’ exist on its own, floating in the cosmos? A naturalist view of reality has no place for it. This simple thought quickly metastasized. I realized that mathematics, the very tool we use to describe reality, is a product of the mind. We’re caught in a loop, explaining a mental creation with another mental creation.

This led me to question all objects. Does a rock on an undiscovered world wait for a mind to grant it existence? If we say it doesn’t—that objects can exist unperceived—then we must logically welcome an infinitude of absurdities. We must accept that heaven, hell, and every other fiction ever conceived might also be “out there,” waiting. This path is an intellectual mess.

The alternative, that the inherently flawed, biased mind is the sole approver of reality, is even more absurd. I tried to invoke Plato’s Theory of Forms, but it felt like the most grandiose of these conveniences—a beautiful, eternal safe house for ideas that has no verifiable address. Every mental construct, from a simple number to Plato’s entire world of Forms, started to feel like a dangling pointer in C language: a reference pointing to a null address.

This is where I first sensed a great divergence. Western thought often tries to build reality from the bottom up—from physics to chemistry, biology, and eventually, consciousness. It’s an emergent model. Eastern thought, I realized, starts and stops with consciousness, because everything we perceive to be other than it is understood to be the grand illusion.

The Mind’s Viral Addiction to Sense

The problem wasn’t the objects; it was the observer. I began to see my own mind as a machine with one primary directive: seek comfort. It seeks comfort in patterns, satisfaction in explanations, and safety in a predictable world. It has a viral addiction to making sense.

This is when I had to revise the Kantian idea that the “fundamental structures of our minds (like space, time, and causation) impose a certain order on our experience.” I realized it’s more radical than that. These structures don’t just order experience; they impose “unreal existence” on it. The very framework of our perception is the engine of fabrication.

How can we possibly “explain” something that doesn’t fundamentally exist? Any science or philosophy that attempts to do so is just one part of the illusion analyzing another. It is a dream character writing a physics textbook about the dream world. The internal logic may be flawless, but the entire enterprise is grounded in unreality.

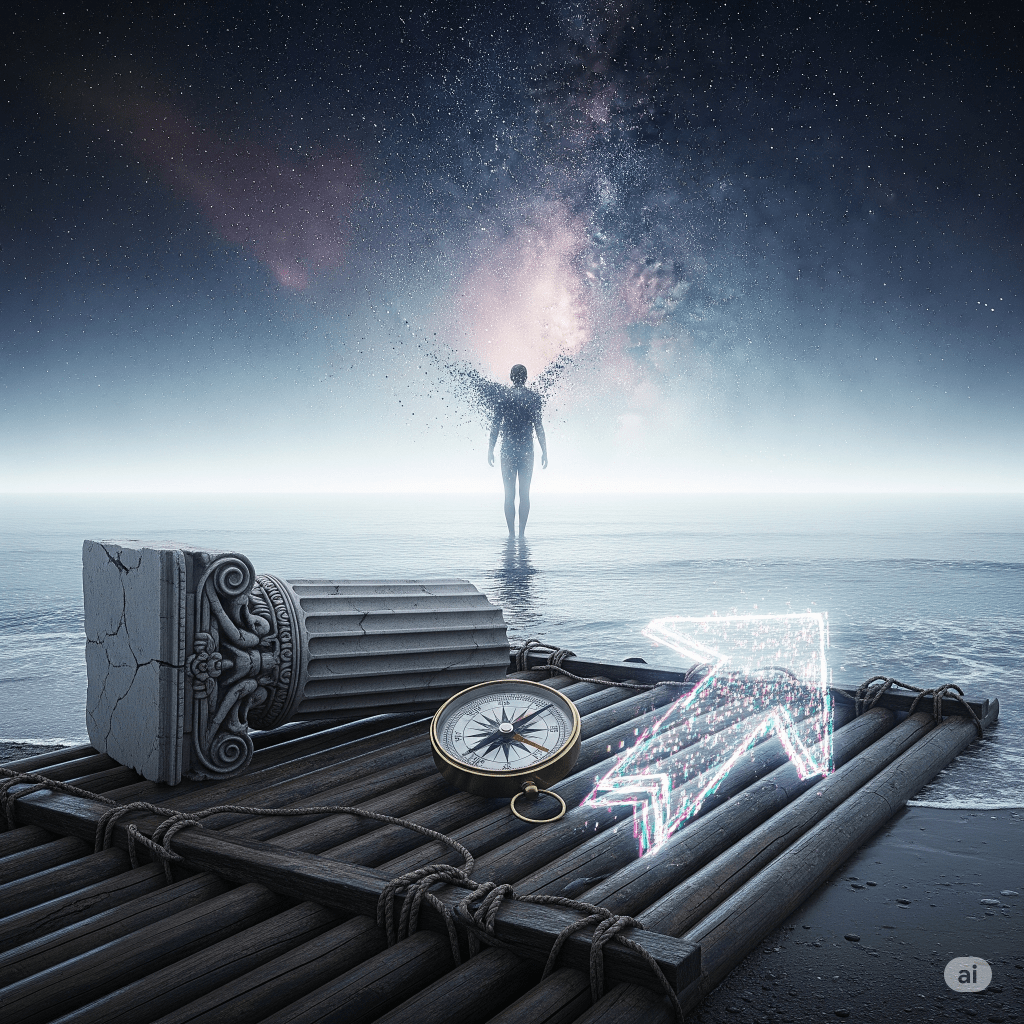

This is the work of Māyā, the cosmic illusion. The world we experience is not ultimately real, but an appearance projected onto a formless screen. The tools we use to navigate it—logic, reason, science—are like the oars and raft in the Buddha’s parable. They are essential for crossing the river of worldly life, but they are not the destination. To mistake them as such is the ultimate folly.

Erasing the Final Pointer

This critical lens, once polished, had to be turned inward. I had dismantled the reality of the external world and the concepts used to describe it. But one final bastion remained: the mind itself.

In computer science, a dangling pointer persists in pointing to memory that has been freed — it still has an address, but the content is erased or overwritten. In our mental life, this is like the illusion of a “self” persisting when its referent — thoughts, plans, memories — have dissolved, leaving behind a phantom. The mind reaches out, but there’s nothing there.

And so, the arc completed itself with one final, necessary erasure.

Thus, for the mind, nothing exists. Not even other minds. The very existence of “a mind” is another unnecessary, forceful, and irrelevant imposition. It is the ultimate dangling pointer, created by our obsession with objectivity. To have an objective world, we feel we must have a subjective self who perceives it. We invent the “I” to make sense of the “that.” It is the final act of comfort-seeking, the creation of a ghost in the machine to give the illusion a witness.

With this, the entire structure of duality collapses. If the object is an illusion, and the subject who perceives it is also an illusion, what is left?

This is where words bend and break. The only “existence,” if we can even call it that, is of a completely different order. It is that which lies “completely beyond” the mind’s grasp. You can give it the Vedantic name: Sat-Chit-Ananda (Being-Consciousness-Bliss).

This is not an object to be known, but the very nature of reality itself, unveiled only when the knower dissolves. It is not something you perceive; it is what you are when perception and the perceiver are both seen as a dream.

The philosophical arc is complete. It is a journey from doubting the world, to doubting the mind, to resting in that which requires no doubt because it is beyond the very framework of knowing. It is the realization that after you leave the raft on the shore, you must also leave behind the “you” that crossed the river. There is only the far shore. Hence, and finally, Non-duality.