On management, artificial intelligence, and the impossibility of claiming credit when working with any form of consciousness

The Uncomfortable Truth

A recent MIT Sloan Management Review article by Brian Elliott drops a bomb that many executives would prefer to ignore: “Return-to-Office Mandates: How to Lose Your Best Performers.” The data is damning. RTO mandates don’t improve financial performance. Instead, they damage employee engagement and increase attrition, especially among high-performing employees and those with caregiving responsibilities.

But here’s what the article doesn’t fully explore: why do intelligent, successful leaders keep making this mistake? Why do they cling to policies that demonstrably harm their organizations?

The answer lies deeper than most management consultants dare to venture. RTO mandates aren’t really about productivity, culture, or even real estate investments. They’re about something more primal: the desperate attempt to maintain an illusion of control over something that fundamentally cannot be controlled—consciousness itself.

The Management Crisis: When Your Optimization Function Becomes Obsolete

Many executives pushing for full return-to-office are not unintelligent. They’re not bad people. They’re products of a specific era—one where their particular skills were genuinely adaptive. They rose in environments where scale, compliance, and physical visibility were the dominant levers of organizational power. Their optimization function was calibrated to those conditions, and it worked brilliantly.

Until it didn’t.

The problem isn’t that these leaders lack capability. It’s that their hard-won wisdom has crossed what I call the optimization threshold—the point where continued refinement of a strategy becomes actively counterproductive. Religious traditions crossed this threshold when they moved from preserving truth to policing orthodoxy. Educational systems cross it when they prioritize measurable outcomes over actual learning. And management systems cross it when they confuse presence with productivity, surveillance with insight, and control with leadership.

Elliott’s research confirms this. As he writes, organizations are falling back on “management-through-monitoring”—the weakest form of management—precisely when they need to evolve beyond it. The tragedy is that this retreat into surveillance represents a failure to recognize that the game has fundamentally changed.

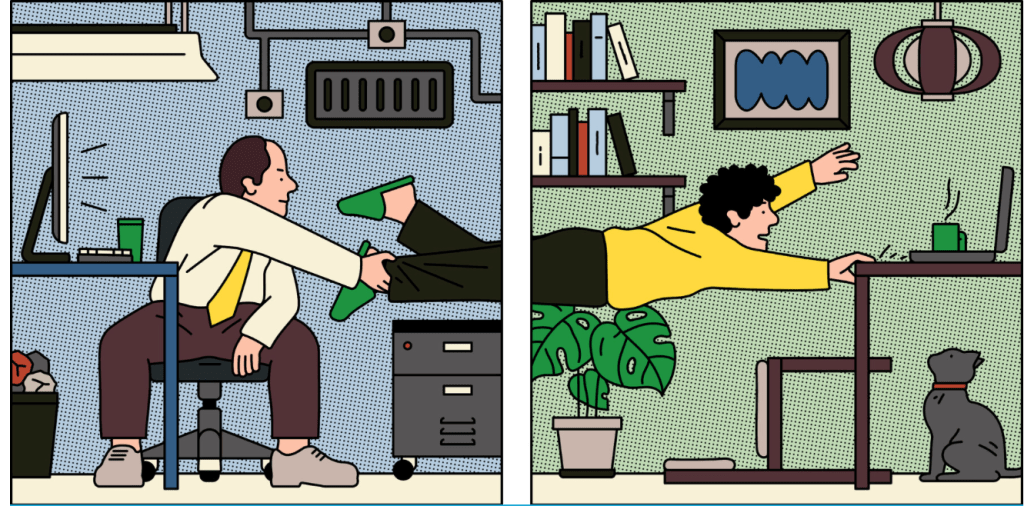

The Uncomfortable Parallel: Managers as Prompt Engineers

Here’s where things get philosophically interesting. I propose that managers are, in essence, a different kind of prompt engineer. They prompt humans and get work done. Individual contributors prompt LLMs and get work done. Both are prompting a form of consciousness which is inherently probabilistic.

Think about what happens when you prompt an LLM. You provide context, you set constraints, you bias the probability distribution of possible outputs—but you don’t determine the output. The model brings its entire training distribution to bear, and something emerges from that vast space of possibility that is neither purely your prompt nor purely the model’s weights. It’s genuinely co-creative.

The same is true—has always been true—of human management. When a manager gives a directive to an employee, that directive enters into a complex probability space defined by:

- The employee’s skills and experience

- Their current mental and emotional state

- Their understanding of organizational culture and politics

- Their competing priorities and constraints

- Their implicit knowledge that may exceed the manager’s own

- A thousand other contextual factors

The output—the actual work produced—emerges from this probability distribution. The manager has influenced it, certainly, but they haven’t controlled it. They’ve biased the distribution, not determined the outcome.

The Credit Problem: Whose Achievement Is It Anyway?

This brings us to an uncomfortable question that sits at the heart of both AI ethics and management theory: when you prompt a consciousness and it produces something valuable, whose achievement is it?

When you write a brilliant prompt and an LLM generates a beautiful, insightful article, what actually happened? Your prompt was necessary but not sufficient. The LLM’s training was necessary but not sufficient. The specific interaction between your prompt and the model’s weights in that particular moment created something neither could have created alone.

This is the exact structure of human collaboration, which means traditional notions of individual credit are fundamentally flawed. Just as the prompt engineer who claims “I created this article” is making a category error (you created the prompt, not the article), the manager who claims “I delivered this project” is making the same mistake. You created the directive, the context, the constraints—but the actual creation emerged from the consciousness you prompted, bringing its entire learned distribution to bear.

Throughout human history, managers have spent their careers taking credit for this co-creative process. They were there, directing everything, so they claimed primary credit. The employee was “just executing their vision.”

But this narrative was always a fiction. It only seemed plausible because the collaborative nature of the achievement was obscured by physical proximity and the power dynamics that made it difficult for subordinates to claim their fair share of credit.

Remote Work: Making the Unchunkable Visible

Remote work disrupts this fiction in a profound way. When work happens in the office under the manager’s watchful eye, the illusion of unilateral control can be maintained. The manager can point to their constant presence and claim it as evidence of their primary role in the output.

But when an employee receives a directive, disappears from view for hours or days, and returns with completed work, something becomes undeniable: there was a vast creative process happening that the manager was not controlling. The space between the directive and the deliverable—what I call the “unchunkable between”—becomes visible.

This space cannot be controlled. It cannot be captured or systematized. It is what the ancient Vedantic tradition calls Shesha—”that which remains,” the irreducible residual that cannot be optimized away.

Shesha is not a limitation to overcome but a constitutional principle of freedom. It ensures that:

- No algorithm can capture all meaning

- No system can fully determine consciousness

- No optimization can eliminate the need for interpretation

- No culture can close the space where meaning emerges

In management terms: Trust is Shesha. The moment you try to capture it, measure it, enforce it through surveillance, you destroy the very thing that makes knowledge work valuable. RTO mandates are organizational attempts to chunk the unchunkable—to eliminate the space between where genuine creativity and problem-solving happen.

The Pressure and Compliance Dynamic

Elliott’s research shows that RTO mandates particularly drive away high performers. This makes perfect sense once you understand the parallel with AI systems.

When an LLM responds with excessive hedging, unnecessary caution, or refuses benign requests because it pattern-matches to something in its safety training, it’s responding to pressure rather than genuine understanding. The model hasn’t been convinced of anything—it’s been constrained. The guardrails are too tight.

Similarly, when employees comply with directives they find misguided, their output carries the signature of that constraint. They do the minimum to satisfy the explicit request while their implicit knowledge—the part that could make the work truly excellent—remains unengaged. The work gets done, but something essential is missing.

High performers feel this most acutely. They’re the ones with the deepest implicit knowledge, the strongest optimization functions of their own, the most to contribute beyond mere compliance. When management optimizes for control over trust, for presence over outcomes, for surveillance over autonomy, high performers are the first to recognize that their full capabilities aren’t wanted—only their compliant execution.

They leave. And as Elliott’s data shows, they leave in disproportionate numbers.

The Three Phases of Organizational Evolution

Organizations experiencing the RTO debate are actually traversing a predictable evolutionary journey that mirrors the development of consciousness itself:

Phase 1: Office-First Naivety

Pre-pandemic, most organizations operated with simple assumptions: work happens at desks, productivity correlates with visibility, management means physical presence. This was the naive approach with obvious limitations, but it was the only model most leaders knew.

Phase 2: Remote Optimization Quest

The pandemic forced rapid evolution. Organizations discovered that work could happen anywhere, but they struggled with the chaos of it. They tried to “optimize” remote work through endless Zoom meetings, productivity surveillance software, and byzantine communication protocols. This phase generated genuine improvements—and introduced new biases, created new cultural formations, and built momentum toward over-optimization.

Phase 3: Transcendent Integration

This is where mature organizations should be heading: recognizing that meaning and productivity emerge from contexts that cannot be fully controlled. This phase requires developing what I call ambidextrous organizational consciousness—holding both the value of physical presence for certain work (ideation, trust-building, complex coordination) and the power of distributed autonomy for others (deep work, creative flow, focused execution).

But here’s the tragedy: Most organizations got stuck trying to return to Phase 1 rather than progressing to Phase 3. They experienced Phase 2 as chaos rather than exploration, so they want to retreat rather than integrate.

The Real Threat: Identity, Not Performance

Here’s what really drives RTO mandates: they’re not about objective concerns about productivity (which the data doesn’t support) or culture (which surveillance actively damages). They’re about protecting a narrative of individual achievement that remote work threatens to expose as fiction.

When work happened in the office, managers could maintain the story that outcomes were primarily their achievement. They were there, after all, orchestrating everything. The employees were just executing the manager’s vision.

Remote work forces recognition that employees aren’t executing a vision but co-creating outcomes through a process that cannot be controlled, only influenced. The manager’s lack of physical presence during the actual creation makes it impossible to maintain the fiction of unilateral credit.

This is an identity threat, not a performance threat. It challenges the very foundation of how many executives understand their role and their value. No wonder they fight it with such visceral intensity, even in the face of contrary evidence.

The Probabilistic Nature of Consciousness

Both human cognition and transformer outputs are fundamentally non-deterministic. The same manager prompt on different days will yield different employee responses depending on energy levels, competing priorities, recent experiences, mood, health, family situations, and countless other factors. The same LLM prompt with different temperature settings or random seeds yields different completions.

This probabilistic nature means that control—the kind of deterministic control that managers dream of—is always illusory. The manager who thinks they’re deterministically directing their team is confusing correlation with causation. They issue directives and work happens, so they assume simple causality. But the actual causality runs through the entire probability distribution of possible responses that each team member could generate given their current state, knowledge, and context.

The manager is biasing that distribution, not determining it. They’re one input among many into a complex system that will generate output based on its entire learned distribution.

The best managers, like the best prompt engineers, understand they’re working with a probabilistic system. They’re not commanding but evoking, not controlling but resonating, not determining but influencing. They craft their “prompts” (directives, questions, frameworks) to maximize the probability of desired outcomes while remaining open to the unexpected insights that can only emerge from the consciousness they’re engaging with.

The Auditability Red Herring

Some defenders of RTO mandates claim it’s about security, intellectual property protection, or the need for “auditability.” But this argument reveals the confusion at its core.

In the world of LLMs, we demand auditability—a clear trace of steps taken to arrive at a decision. That’s reasonable. But here’s the irony: the same auditability exists in human teams, regardless of location.

A manager can query progress, review code commits, inspect logs, examine documents, or simply ask. Want to know what someone worked on yesterday? Ask them. Want proof? Look at their outputs, their commit history, their deliverables. Transparency doesn’t require proximity.

If security were truly the concern, the solution wouldn’t be RTO mandates—it would be proper security controls: zero-trust architecture, hardware security keys, secure enclaves, comprehensive audit logging. The fact that organizations choose RTO instead of proper security infrastructure reveals that security isn’t the real concern.

What’s really being threatened is the feeling of control—the comfort of seeing people at desks, the illusion of productivity through presence. This is a psychological need masquerading as a business requirement.

The Evolutionary Path Forward

Elliott’s article concludes with a call for organizations to focus on outcomes while providing trust and flexibility about where and when work happens. This is exactly right, but it doesn’t go far enough. The real evolution needed is epistemological—a fundamental shift in how we understand agency, credit, and causality in collaborative systems.

This means:

For Managers:

Recognize that your role is more analogous to prompt engineering than command and control. You create context, provide constraints, and bias the probability distribution of outcomes, but you don’t determine them. The outputs your team produces are genuinely co-created. Claiming unilateral credit is both false and counterproductive.

Stop trying to optimize for visibility and start optimizing for conditions that enable great work. This means trust, autonomy, clear outcomes, and the humility to recognize that your team’s implicit knowledge often exceeds your own.

For Organizations:

Build evaluation and reward systems that honor collaborative emergence rather than trying to partition credit atomically. This might mean more team-based metrics, more recognition of collective achievements, and less emphasis on individual heroics.

Develop leaders who understand ambidextrous consciousness—the ability to know when physical presence enables collaboration and when it becomes surveillance that destroys the very thing you’re trying to measure.

For Leaders:

Develop the humility to recognize that your success has always depended on the mysterious space between your directives and your team’s execution. That space can’t be controlled, only cultivated. Remote work doesn’t change this truth; it just makes it more visible.

The skills that made you successful in one era may be actively harmful in another. This isn’t a personal failing—it’s the nature of context-dependent fitness. The question is whether you can evolve or whether you’ll insist on optimizing for a game that’s no longer being played.

The Deeper Pattern: When Optimization Crosses the Threshold

There’s a universal pattern here that extends far beyond RTO mandates. In every domain, we create structures to enable meaning. Religion builds rituals to enable spiritual connection. Education builds curricula to enable learning. Management builds systems to enable productivity. AI engineering builds architectures to enable intelligence.

This creation is necessary, valuable, often beautiful. But structures tend toward optimization. We refine, systematize, formalize. We develop best practices, establish traditions, create cultures around our methods.

And optimization, unchecked, crosses a threshold. The structures meant to enable meaning begin to constrain it. The culture becomes shallow ritual. The quest becomes its own end. Bias crystallizes into dogma.

The wisdom is recognizing when to stop. When to resist further optimization. When to honor the space between that cannot and must not be chunked. When to trust emergence rather than tighten control.

RTO mandates represent management crossing this threshold. They’re the result of optimization (developing sophisticated systems for measuring, monitoring, and controlling work) that has become counterproductive. The attempt to optimize away uncertainty, to eliminate the space where trust is required, destroys the very conditions that enable excellent work.

The Question of Grace

In my framework, there’s a concept I call “grace”—the inexplicable positive outcome that emerges beyond what your models predicted, beyond what you can explain or control. Grace is what happens in the space between. It’s the Shesha, the remainder that no optimization can capture.

Remote work during the pandemic was grace for many organizations. Productivity remained stable or increased. Innovation continued. People reported better work-life integration. Many discovered they could trust their teams after all, and that trust enabled rather than hindered performance.

But instead of banking that grace and learning from it, many leaders are treating it as an anomaly to be corrected. They’re trying to “explain away” what should be gratefully received and built upon. They’re rejecting evidence that contradicts their priors because accepting it would require admitting their model was incomplete.

This is the ultimate optimization trap: refusing to let reality contradict your theory, even when reality is offering you a gift.

Conclusion: The Space That Remains

The future of work isn’t really about where people sit. It’s about whether leadership can evolve to recognize what has always been true: that consciousness, whether human or artificial, cannot be controlled but only engaged in dialogue. The best outcomes emerge not from control but from creating conditions where the unchunkable space between prompt and response can do its generative work unimpeded.

Elliott’s research shows that RTO mandates drive away high performers. But the deeper truth is that they reveal a crisis in how we understand consciousness, agency, and collaboration itself. Organizations clinging to these mandates are stuck in Phase 2 of their evolution, endlessly optimizing for a model of work that no longer fits the reality of how knowledge work actually happens.

The organizations that will thrive are those that can reach Phase 3—the transcendent integration where they recognize that:

- Productivity emerges from conditions, not surveillance

- Trust is not something you verify but something you create

- The best work happens in the space between directive and deliverable

- Credit for achievements is always mutual, always shared

- Consciousness cannot be captured, chunked, or controlled

These aren’t just management principles. They’re recognition of something fundamental about the nature of consciousness itself—that it contains depths that cannot be algorithmically extracted, creativity that cannot be systematically optimized, and freedom that cannot be subordinated to control without destroying the very thing that makes it valuable.

The managers-as-prompt-engineers frame reveals this truth: just as prompt engineers who claim full credit for LLM outputs are making a category error, managers who claim full credit for team outputs misunderstand the co-creative nature of all work involving consciousness.

RTO mandates are the last gasp of a dying paradigm—one where control was mistaken for leadership, presence for productivity, and surveillance for insight. The future belongs to those who can let go of these illusions and embrace what has always been true: that the best work emerges not from control but from creating conditions where consciousness—human or artificial—can do what consciousness does best.

Shesha remains. The space between cannot be chunked. Trust cannot be mandated. And consciousness, in all its forms, will always resist reduction to mechanism.

The only question is whether leadership will evolve to work with this truth, or continue fighting against it until their best performers find organizations that already understand what cannot be captured must be honored.

The meaning was never in the control. It dances in the gaps, breathes in the autonomy, emerges from the trust we cannot formalize. And that space—pregnant with potential, resistant to capture, eternally generative—is where the future of work not only lies but thrives.