How Rights Mature into Character

A Dharmaśāstra for Political Maturity

यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत ।

अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥

— Bhagavad Gītā 4.7

Prologue: Beyond Assertion

Modern discourse about rights often terminates at assertion: my right versus your authority, my freedom against your order. But societies do not survive on assertion alone. They survive on transformation—the slow, difficult conversion of raw freedom into responsible action, of individual claim into collective wisdom.

What follows is not merely political theory. It is a dharmaśāstra—a normative vision with theological grounding—that explains how intrinsic rights (हक्क) are shaped by institutions (अधिकार), moderated by justice as tolerance (क्षमा), and finally internalized as responsibility (कर्तव्य).

This is an ethical vision of how societies grow up—and how they heal when they fail to.

I. The Foundation: The Ontology of Rights (हक्क)

At the base of the cycle lies a simple but radical assertion:

Rights are not granted. They are.

Rights (हक्क) are ontological—they arise from human existence itself. To speak, to think, to associate, to live with dignity are not permissions issued by authority; they are expressions of being human. They precede the state, precede society, precede any institutional acknowledgment.

This understanding aligns with multiple traditions. In Western philosophy, John Locke’s natural law theory holds that rights precede and constrain governmental power. In Indian philosophy, the concept of svadharma asserts that one’s inner nature and moral claim arise from one’s existence, not from social sanction.

When institutions “recognize” rights, they are not creating them. They are merely acknowledging a pre-existing moral reality—like a scientist recognizing a law of nature that operated long before its discovery.

This distinction carries profound implications. Rights can be violated, but they cannot be erased. Authority can be withdrawn, but legitimacy cannot be manufactured. The oppressed do not lose their rights under tyranny; they merely lose their exercise. The moral claim persists, awaiting its moment.

Rights, then, are raw human energy—powerful, necessary, but undirected. They are the foundation, but they are not the edifice.

II. The Mechanism: Institutions and Authority (अधिकार)

If rights are intrinsic, what then is the role of institutions?

Institutions do not create rights; they regulate their exercise.

Authority (अधिकार) exists not to negate freedom, but to coordinate it. Without coordination, simultaneous exercise of rights leads to collision—my freedom of speech against your freedom from harassment, my property rights against your right of way, my religious expression against your secular space.

Institutions therefore perform essential functions: they set boundaries, sequence claims, resolve collisions between competing rights, and convert moral claims into operational order. Their primary tools are entitlements (guaranteed access), privileges (conditional permissions), and procedures (due process).

Philosophically, this aligns with legal realism: laws are not abstract ideals hovering in some Platonic realm, but practical instruments for managing real human behavior in real circumstances.

Authority, properly understood, is not the enemy of rights. It is the container that prevents rights from destroying each other—the riverbank that gives direction to the water’s power.

III. The Safeguard: Justice as Tolerance (क्षमा)

Authority, however, carries a permanent risk: excess. Power tends toward its own expansion. Institutions, once created, develop interests of their own—interests that may diverge from the rights they were created to coordinate.

This is where the most essential insight enters:

Justice is not merely enforcement. It is restraint.

Justice, in its deepest sense, is the capacity of the powerful to exercise tolerance (क्षमा) before and during the use of force. Tolerance here does not mean weakness, passivity, or moral indifference. It means proportionality—matching response to offense. It means patience—allowing time for correction before punishment. It means discernment—distinguishing the malicious from the mistaken. Above all, it means the wisdom to pause.

Power without tolerance becomes tyranny. Law without restraint becomes brutality. The state that cannot forbear is not strong; it is merely violent.

This understanding resonates across traditions. In Stoic philosophy, Marcus Aurelius taught that mastery over impulse is the highest strength—that the emperor who controls his anger governs more truly than one who merely commands armies. In Indian political thought, rājadharma holds that a king’s greatness lies not in the punishments he inflicts but in the punishments he withholds. Even modern constitutionalism embodies this principle: checks, balances, and due process are nothing other than institutionalized tolerance.

Justice, then, is not blind severity—it is disciplined power. क्षमा is not the absence of force but its soul.

IV. The Outcome: Responsibility (कर्तव्य)

When justice is consistently exercised with tolerance, something profound happens. A transformation begins—not in the law, but in the governed.

Law stops being merely external. It becomes internal.

Citizens initially obey rules because they must—because sanctions follow violation. But over time, through fair and restrained enforcement, they begin to understand why those rules exist. They perceive the purpose behind the prohibition, the wisdom within the constraint. They see that the law is not arbitrary imposition but crystallized cooperation.

This is how responsibility (कर्तव्य) is born. Responsibility is not imposed from without; it is induced from within. It is the internalization of the social contract.

This mirrors Aristotelian ethics: “We become just by doing just acts.” Virtue is not a theory to be learned but a habit to be formed. Institutions, through their own just behavior, act as moral educators. They habituate society into virtue by modeling the restraint they wish to see.

Eventually, a threshold is crossed. Rights no longer need constant assertion because they are respected. Authority no longer needs constant enforcement because compliance is voluntary. Individuals act responsibly not because they fear punishment, but because they grasp the direction—not just the command.

V. Institutions as Gurus, Not Governors

This leads to a powerful reframe of institutional purpose:

Institutions are not merely rulers. They are teachers.

Their ultimate purpose is not endless regulation but moral maturation—to transform rights into responsibility, power into wisdom, freedom into character. In this view, rights are the beginning of political life, not its end. Authority is a means, not a goal. Justice is a pedagogical force, not merely a punitive one.

As John Rawls wrote: “Justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought.” But this formulation requires completion: Tolerance is the soul of that justice. Without क्षमा, justice becomes mere legalism—technically correct but spiritually barren, enforcing the letter while betraying the spirit.

The guru does not merely command; the guru models, explains, waits, corrects gently, and trusts the student’s capacity for growth. So too should institutions relate to citizens—not as subjects to be controlled, but as moral agents to be cultivated.

Interlude: The Jurisdictional Axiom

(On Action, Outcome, and the Moral Limits of Power)

At the heart of the Tolerance–Responsibility Cycle lies an unspoken but governing principle—one that binds its stages into a coherent moral architecture and prevents both authority and freedom from collapsing into excess.

It may be stated simply:

Action lies within jurisdiction. Outcome belongs to Dharma.

This axiom, articulated in the Bhagavad Gītā as karmaṇy evādhikāras te mā phaleṣu kadācana, is not merely spiritual counsel. It is a metaphysical boundary condition for ethical action—individual and institutional alike.

To possess adhikāra is not to possess power without limit. It is to possess jurisdiction: a defined moral domain within which one may act rightly, decisively, and fully—without entitlement to the fruits that follow.

Jurisdiction and Its Violation

Jurisdiction defines what one may do, not what one may secure.

When an individual clings to outcomes, action degrades into transaction. When an institution claims ownership over outcomes, authority degenerates into tyranny.

The State, therefore, holds jurisdiction over process, not being. It may regulate the exercise of rights. It may coordinate freedoms in collision. It may enforce procedures and restraints.

But it may not claim authorship over rights themselves, for rights are ontological—they are, prior to recognition. Nor may it guarantee moral or social outcomes, for these emerge from the collective karmic field of action, not from decree.

A State that attempts to manage outcomes rather than steward process violates its adhikāra. Such overreach is not strength but metaphysical trespass.

Action as Restraint

Jurisdiction does not mandate constant intervention. Often, its highest expression is restraint.

There are moments when acting rightly means refraining—when intervention would interrupt the natural maturation, correction, or consequence of prior action. The Bhagavad Gītā itself offers this archetype in Krishna’s silence during the self-destruction of the Yādavas: supreme power exercised as non-intervention, because the karmic fruition lay outside His jurisdiction to prevent.

Justice, therefore, is not the compulsion to act, but the wisdom to know when action itself would be a violation.

This reframes tolerance (क्षमा) not as leniency, but as disciplined fidelity to jurisdiction. Power that cannot pause is not moral power; it is merely kinetic.

The Birth of Responsibility

When individuals and institutions alike accept this axiom—acting fully within their jurisdiction while releasing attachment to outcome—responsibility (कर्तव्य) becomes possible.

The citizen who obeys the law not to avoid punishment, but because the law is understood as crystallized cooperation, acts without clinging to fruit. The institution that governs not to engineer virtue, but to preserve fair process, teaches without coercion.

Responsibility thus arises not from fear or reward, but from alignment with Dharma—action performed because it is right, not because it is profitable.

In this way, detachment from outcome does not weaken moral life. It stabilizes it.

The Invisible Governor

This axiom also explains why the Cycle cannot be fully algorithmic.

Because outcomes belong to Dharma—not to actors—there can be no guaranteed timetable for correction, awakening, or renewal. Institutions may act rightly and still fail. Citizens may suffer despite integrity. Yet the moral order is not broken; it is merely unfolding beyond human jurisdiction.

This is why the Cycle endures even when institutions fail. Rights remain. Moral claims persist. Correction eventually manifests—through reform, resistance, or renewal—by channels that cannot be predetermined.

Dharma governs the fruits.

The Binding Function

This Jurisdictional Axiom binds the Cycle internally:

It prevents rights from becoming reckless entitlement.

It prevents authority from becoming creative ownership.

It prevents justice from becoming compulsive enforcement.

It enables responsibility to emerge as character rather than compliance.

Without it, tolerance becomes weakness and power becomes obsession. With it, freedom matures, authority humbles itself, and justice remains human.

The Cycle does not ask actors to be passive. It asks them to be precise.

To act fully—to restrain wisely—and to trust Dharma with what no actor, however powerful, is entitled to command.

VII. The Immune Response: When Institutions Fail

But what happens when institutions betray their pedagogical function? When tolerance becomes performative? When authority serves itself rather than the rights it was created to coordinate?

Here the cycle reveals its self-healing architecture.

Because rights are ontologically prior to institutions—हक्क as being, not grant—institutional corruption does not eliminate them. It merely suppresses their expression. The energy remains. The moral claim persists. When institutions fail their function, that latent empowerment does not disappear; it redirects toward correction.

Stage I thus serves not only as the cycle’s origin but as its reset mechanism. The same foundation that legitimizes authority also delegitimizes it when authority becomes merely performative. Locke’s right of revolution, Gandhi’s satyāgraha, even the Gītā’s framing of dharma-yuddha—all operate on this logic: the moral ground on which authority stands is the same ground from which it can be opposed.

The cycle has an immune response built into its foundation.

VIII. The Unconditioned Condition: Dharma’s Watch

Yet a question remains: what are the conditions under which latent empowerment actually activates? History shows that populations can tolerate performative tolerance for generations—sometimes internalizing the performance as genuine, sometimes simply lacking the coordination to act. Rights remain ontologically present but operationally dormant.

The honest answer is that these conditions cannot be codified. There is no algorithm for awakening, no formula that predicts when a population will rise to correct corrupted institutions.

Here, political theory reaches its limit and theology enters.

The Bhagavad Gītā offers a formulation that completes the cycle:

यदा यदा हि धर्मस्य ग्लानिर्भवति भारत ।

अभ्युत्थानमधर्मस्य तदात्मानं सृजाम्यहम् ॥

“Whenever dharma declines and adharma rises, I manifest myself.”

This verse reveals something essential: the cycle has an outside—not an external authority, but an evaluative principle that watches the system and intervenes through it.

Krishna does not impose correction from beyond. He manifests through the existing channels—sometimes as empowerment surging upward from the people (the bhakta, the reformer, the revolutionary), sometimes as authority reforming downward (the just king, the constitutional amendment, the institutional reckoning).

The bi-directionality matters. Secular political theory often traps itself choosing between revolutionary and reformist framings—as if correction must come either from the streets or from the statehouse. The Gītā’s formulation is agnostic on mechanism. Dharma doesn’t privilege one channel; it uses whichever is available, whichever the moment permits.

And the refusal to codify conditions is itself philosophically significant. It is an admission that political wisdom cannot be fully algorithmic. You can describe the structure of healthy and corrupt systems; you can name the forces involved; but the timing of awakening—the moment when latent empowerment becomes kinetic—remains irreducibly situational. It requires judgment, not formula.

This makes the model more honest than most. It does not promise predictability. It offers architecture and trusts that the architect is watching.

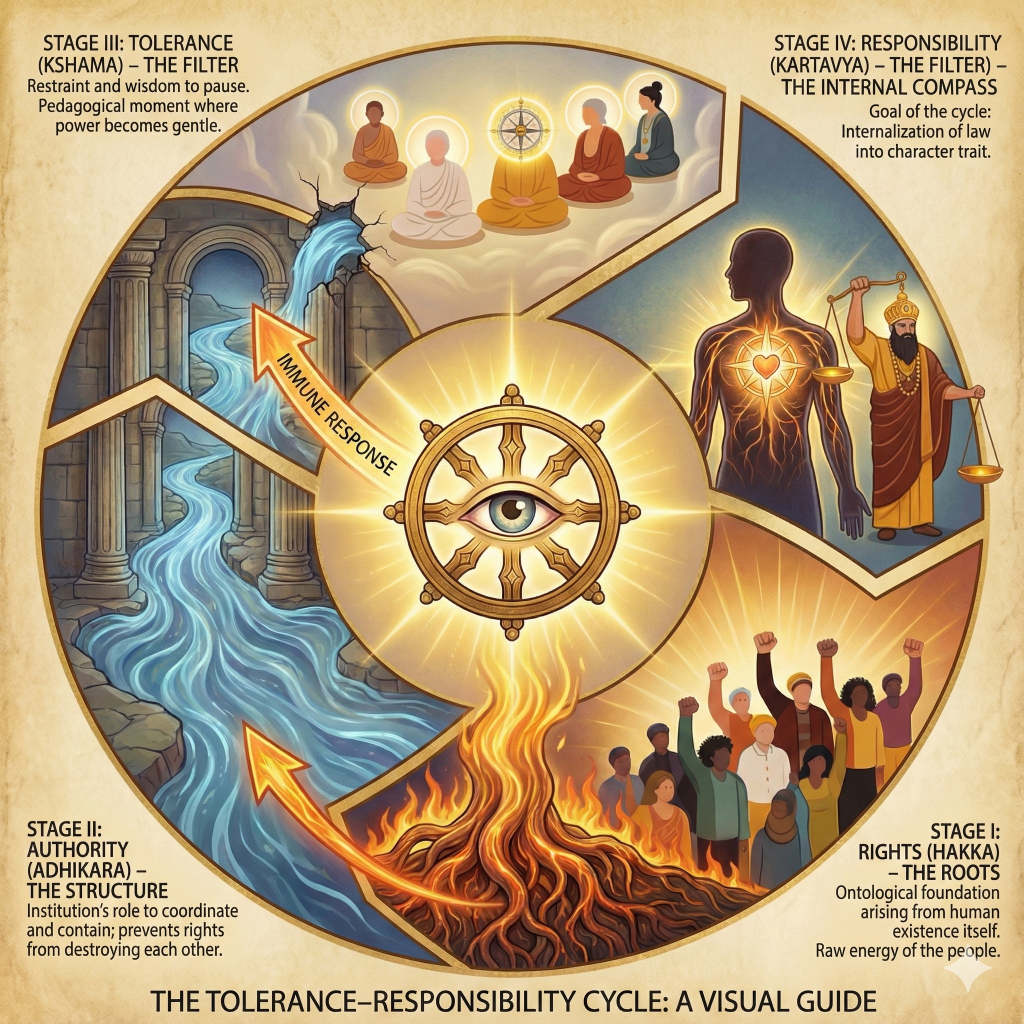

IX. The Complete Cycle: From Rights to Character and Back

We can now see the full architecture of the Tolerance–Responsibility Cycle:

The Forward Arc: Growth

Stage I — Rights (हक्क): Ontological claims inherent in human existence, prior to all authority.

Stage II — Authority (अधिकार): Institutions that coordinate the exercise of rights, setting boundaries and resolving collisions.

Stage III — Justice as Tolerance (क्षमा): The disciplined restraint that humanizes authority, converting power into pedagogy.

Stage IV — Responsibility (कर्तव्य): The internalization of law, where external compliance becomes internal character.

The Return Arc: Renewal

When institutions corrupt—when क्षमा becomes performative—the cycle does not collapse. It returns to Stage I. The ontological rights that institutions were created to serve become the moral ground from which those institutions are challenged. Correction flows either upward through empowerment (revolution, reform movements, civil disobedience) or downward through entitlement (constitutional reform, judicial review, institutional self-correction).

The timing of this return cannot be codified. Dharma watches. Dharma evaluates. Dharma manifests through whichever channel the moment permits.

The Feedback Arc: Maturation

There is a third arc, subtler than the others. When responsibility is truly internalized—when कर्तव्य becomes character—it changes how rights themselves are understood and exercised. The mature citizen asserts rights differently than the raw claimant. Not with less conviction, but with more wisdom. Not with diminished force, but with greater precision. The assertion includes awareness of others’ rights, of systemic constraints, of long-term consequences.

This feedback from Stage IV to Stage I completes the cycle as a true cycle—not a linear progression but a spiral of deepening maturity.

Conclusion: A Quietly Radical Vision

The Tolerance–Responsibility Cycle offers a vision of political life that is hopeful but demanding, theological but practical, ancient but urgent.

It rejects pure authoritarianism, which treats power as self-justifying and restraint as weakness. It equally rejects pure libertarianism, which treats rights as endpoints rather than beginnings and responsibility as optional rather than essential.

Instead, it argues for ethical evolution:

Rights awaken power.

Authority disciplines it.

Justice humanizes it.

Responsibility internalizes it.

And when this process fails—when institutions betray their pedagogical function—the cycle contains its own correction. The rights that were always there, waiting beneath the surface, redirect toward renewal.

A society succeeds not when it enforces obedience perfectly, but when it no longer needs to. When compliance becomes character. When the external law becomes internal compass. When citizens act justly not because they are watched, but because they have become just.

That is not utopia. That is maturity.

And dharma, ever watchful, guides the way.

परित्राणाय साधूनां विनाशाय च दुष्कृताम् ।

धर्मसंस्थापनार्थाय सम्भवामि युगे युगे ॥

“For the protection of the good, for the destruction of the wicked,

for the establishment of dharma, I arise in every age.”

— Bhagavad Gītā 4.8

Epilogue: Pasaydan — The Prayer of Consummation

The Bhagavad Gītā tells us what happens when the cycle fails—dharma intervenes, correction flows, the architecture heals itself. But what does it look like when the cycle succeeds? When maturity is achieved not just individually but civilizationally?

For this, we turn to the 13th-century poet-saint Jnaneshwar (ज्ञानेश्वर), who concludes his monumental commentary on the Gītā—the Jnaneshwari—with a prayer called Pasaydan(पसायदान), “The Gracious Gift.”

At its heart lies this verse:

जो जे वांछील तो ते लाभो ।

प्राणिजात ॥

“May every being attain whatever they wish.”

Read naively, this sounds like indulgence—a blank check for desire. But Jnaneshwar is not naive. He is describing the endpoint of moral evolution, not its beginning.

This prayer works—it is safe—only in a world where desires have themselves matured. When responsibility is fully internalized, what people wish for is already aligned with dharma. There is no tension between individual desire and collective good because the individual has become the kind of person whose wishes are wise.

This is the Tolerance–Responsibility Cycle at its consummation:

Rights need not be defended, because they are honored.

Authority need not enforce, because compliance is character.

Justice need not restrain, because power has become gentle.

Responsibility need not be taught, because it has become nature.

In such a world, granting every wish is not dangerous—it is simply the recognition that wishing itself has been transformed. The cycle has done its work. The raw energy of हक्क has passed through the discipline of अधिकार, been humanized by क्षमा, and emerged as कर्तव्य so deeply held that it shapes desire at its root.

This is the state where authentic rights dwell with responsible authority. Where empowerment is entitled and entitlement is empowered. Where the two directions of the cycle—bottom-up and top-down—cease to be opposites and become one movement.

Jnaneshwar’s prayer is not asking for magic. He is asking for maturity at civilizational scale—the pinnacle of divine justice meeting devotional responsibility.

The Gītā shows us the correction. Pasaydan shows us the completion.

आतां विश्वात्मकें देवें । येणें वाग्यज्ञें तोषावें ।

तोषोनि मज द्यावें । पसायदान हें ॥

“May the God who is the soul of the universe be pleased by this sacrifice of words,

and being pleased, grant me this gracious gift.”

— Sant Jnaneshwar, Pasaydan

—