A meditation on saving, stinging, and the interpreter who must die

There’s a parable you’ve probably heard.

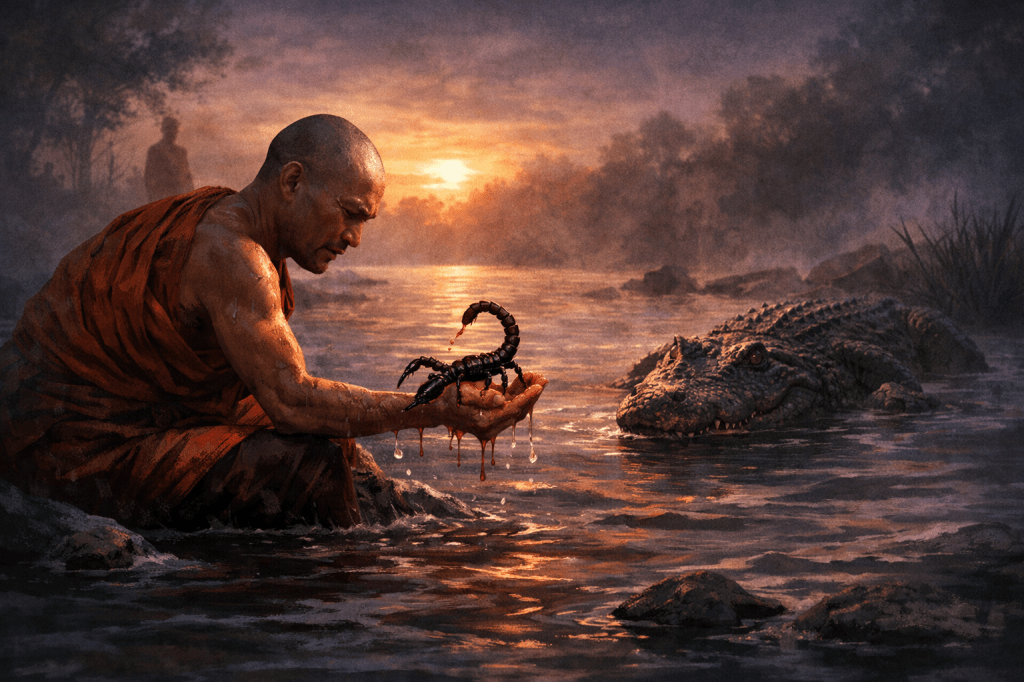

A monk sees a scorpion drowning in the river. He reaches down to save it. The scorpion stings him. He reaches again. Stung again. This continues — compassion meeting venom, over and over — until finally the scorpion is safe on the bank.

A passerby, watching this bloodied persistence, asks: “Why do you keep saving it when it keeps stinging you?”

The monk replies:

“It is the scorpion’s nature to sting. It is my nature to save. Why should I abandon my nature because he follows his?”

This is a beautiful story. It teaches endurance, compassion, the quiet dignity of refusing to be changed by cruelty.

But I want to offer a different reading.

The Roles We Assign

Here’s what troubles me about the traditional interpretation: it assumes we know who the monk is and who the scorpion is.

The monk thinks he is saving a drowning creature. But consider the scorpion’s perspective for a moment. The scorpion, unable to swim, is in the water. A giant hand keeps grabbing it, pulling it through the water, squeezing it. From the scorpion’s view, this might not feel like rescue. It might feel like interference. Let me swim, the scorpion might be thinking. Stop grabbing me.

The stinging isn’t ingratitude. It’s protest. It’s communication. It might even be warning: There are crocodiles in this river, you fool. Get out.

But the monk, certain of his role, interprets every sting as confirmation of his own nobility and the scorpion’s fallen nature.

Who assigned these roles? The storyteller. The interpreter. The one who stands outside the water, watching, and decides what the story means.

A Personal River

I am forty-two years old.

When I was twenty-five, my father told me to become an entrepreneur. I refused. I took a job as a software developer, the “safe” path, the salaried life. He was disappointed.

Seventeen years later, I have a decent home. No debt. A wife. A daughter. A handsome salary. By most measures, I built something.

Recently, I found an opportunity — a US-based company willing to pay thirty dollars an hour for two hours of daily consulting work. It would have been additional income, a small entrepreneurial step while keeping my stability.

When I told my father, he said: “We need to be ethical.”

He meant my employment contract, which restricts outside work. Conflict of interest. So I let the opportunity pass.

Then I began thinking about what he had originally wanted — starting my own business. A consulting practice. Perhaps it was finally time.

His response? “Think of your family’s future. Why break certainty and invite uncertainty at this age?”

At twenty-five, with nothing to lose and everything to gain, he wanted me to risk. At forty-two, with a foundation to leverage and protect, he wants me to stay safe.

Both positions claim to be protection. Both claim to be wisdom.

But which one is saving, and which one is stinging?

The Reversal

Here’s what I’ve come to understand: the roles of monk and scorpion are not fixed. They are assigned by perspective, for the ego’s comfort.

My father sees himself as the monk — reaching into the dangerous waters of my decisions, trying to save me from drowning in naivety or recklessness or ethical compromise. When I don’t listen, when I push back, he experiences it as stinging. Ingratitude. Perhaps even insult.

From my side, the picture inverts completely. I see him as the one stinging — his warnings, his objections, his shifting goalposts feel like venom that paralyzes action. I think I am the monk — trying to save my family’s future, trying to pull us toward something better, getting stung for my efforts.

We are both standing in the river, absolutely certain we know who is drowning and who is saving.

We are both wrong.

The Crocodile

Here’s what the traditional parable leaves out: there’s a crocodile in the river.

The monk and scorpion are so absorbed in their drama — the saving, the stinging, the nature of each — that neither notices what’s approaching. The crocodile doesn’t care about anyone’s nature. It doesn’t care who is compassionate and who is venomous. It doesn’t adjudicate the moral debate.

It simply arrives.

What is the crocodile? It’s uncertainty. Fate. The eventuality that neither caution nor courage can prevent. My father’s warnings won’t stop it. My ambitions won’t outrun it. It swallows the careful and the bold with equal indifference.

The story argues about roles and natures while something larger makes the entire drama a footnote.

But hang on! The crocodile has a second face as well.

The Death of the Interpreter

The crocodile is also enlightenment.

Not the soft, comfortable enlightenment of greeting cards and meditation apps. The violent kind. The kind that kills.

But what does it kill? Not the monk. Not the scorpion.

It kills the interpreter.

The interpreter is the one who stands outside the story, assigning meaning. “The monk represents compassion. The scorpion represents base nature. The lesson is patience.” The interpreter needs the parable to have roles, morals, applications. The interpreter needs to be right about what the story means — and therefore, right about who is the monk and who is the scorpion in any given situation.

The interpreter is the ego.

When the crocodile comes — whether as fate or as awakening — it doesn’t resolve the debate between monk and scorpion. It ends the debate entirely by consuming the one who needed the debate to exist.

My father and I can spend another twenty years arguing about who was right at twenty-five, who is right at forty-two, who is saving and who is stinging. We can accumulate evidence for our respective cases. We can rest on our respective hills.

Or the crocodile can take the interpreter, and something else can remain.

What Remains

When the interpreter dies — when the need to assign roles and meanings and lessons dissolves — what’s left?

Just this: A life worth living.

Not a life spent proving my father wrong. Not a life spent proving him right. Not a life of being the dutiful monk or the misunderstood scorpion. Not a life of accumulating evidence for my case.

Just a life. Lived. Fully. Without the narrator running underneath, constantly explaining what everything means and who is winning the moral argument.

The crocodile, whether it comes as failure or success, as death or awakening, finds you in the water — not on the bank, narrating.

Swimming Without a Story

Perhaps this is what we can offer those we love — not victory in the monk-scorpion debate, but release from it.

My father doesn’t need to be right about what he said when I was twenty-five. He doesn’t need to be right about what he’s saying now. I don’t need him to be wrong. I don’t need to be the misunderstood hero of my own story, stung by those who should support me.

The roles can fall away.

What’s left is a man in his forties, in a river, swimming.

Maybe toward something. Maybe away from something. Maybe just swimming because that’s what you do when you’re in water and alive.

The crocodile is coming for all interpretations.

The monk keeps saving. The scorpion keeps stinging. And neither of them notices what’s approaching, because they’re too busy being right about their natures.

But if you can let the interpreter die before the crocodile arrives — if you can stop narrating your own life long enough to actually live it — then something strange happens.

The water is just water. The swimming is just swimming. The risk is just risk. The love is just love.

And a life worth living doesn’t need a parable to justify it.

It simply is.

Leave a comment